Are some companies happy to risk their reputations and PR

until caught by press and forced by public outcry?

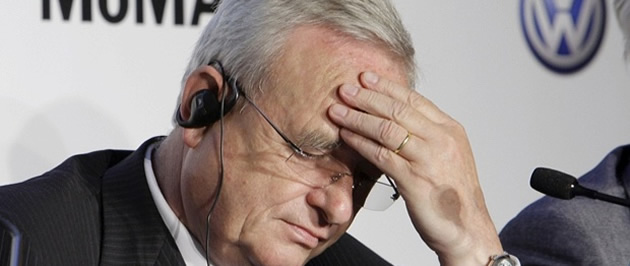

‘Volkswagen in meltdown over faked test.’ ‘WH Smith forced to end hospital shop rip-off. ’ are the two front page stories on The Times today, Wednesday 23 September. Meanwhile in Metro, there is “Outrage as tycoon ups cost of Aids drug from £9 to £500.”

These no doubt unwelcome negative headlines put the spotlight on commercial practices that have stirred up the press and the public and severely damaged the brands’ reputations in the minds of potential customers. They are also providing testing crisis PR work for their PR and communications teams.

There have been a steady stream of stories recently where the media has revolted against what it perceives – reflecting what it believes is public opinion – to be unacceptable commercial activities.

The roll of shame is lengthy; charities exploiting the generosity of pensioners and pressuring them to donate more; airport shops unnecessarily demanding passenger boarding cards so that they can claim VAT back on sales to boost their profits on already opportunistically high prices. They joined the hotels at Kings Cross who infuriated distressed passengers by suddenly doubling their room prices when Eurostar trains were cancelled because a refugee was killed on the track.

The common factor is that their management were putting the brand’s reputation at risk, even of losing some business and sometimes being fined, but decided to proceed, presumably because the commercial opportunities were so great.

Alongside these are the many items on BBC Watchdog and in the national press personal finance pages. Every week there are companies who only give in and refund a customer after a journalist has intervened and shamed them into paying.

The PR question

Yes, there is no denying the principles of supply and demand and recognising the influence of market forces, but somewhere there is a line, a limit – and should or should not a company draw it themselves rather than wait for press, public, legal or regulator pressure to tell them when they have crossed it?

From a PR perspective, these stories raise many interesting questions.

· Were all the pros and cons of the potential decision and its outcomes, including all the PR elements, considered thoroughly before proceeding? And then ignored?

· Did the PR team put the possible negative consequences strongly?

· Were all the potential financial consequences, including potential long term loss of business, fines and the cost of rebuilding the reputation, all calculated?

· Was the decision purely based on a financial equation in which the likely profit far outweighed the possible costs, so it was simply worth the risk?

It would be fascinating to find out but, unless there is a public enquiry or a whistle-blower risks their career by coming forward, we shall never know.

In light of these examples, here are three more final PR questions that everyone should perhaps consider.

· Should a company ever resist public pressure or ignore potential public opinion. If so when?

· Should PR and reputation issues really be assessed according to some financial cost? Are some issues too important, no matter what the money is at stake? How important are morality and ethics?

· Where do you draw the line? What behaviours or policies, business practices or opportunities should an organisation never take up, even if the commercial benefits are vast, even if, for instance, they would save it from going under?

Comments are closed.